Please note this policy is under review following the publication of Working Together to Safeguard Children, 2023.

Last reviewed November 2023.

Date of next review November 2026.

1. Introduction

The Sussex Joint Agency Protocol for Unexpected Child Deaths was originally published in 1999. This latest version updates the Sussex Child Death Review Practice Guidance 2020 and covers all child deaths. It takes into account the following:

These documents contain national recommendations relating to the investigation and reviews of child deaths.

2. Legislative Framework / Core Standards

The corporate responsibilities for child death reviews are explicit and are predominantly informed by legislation and national directives. The Sussex Child Death Review Partnership is required to fulfil its legal duties under the Children Act 2004, as amended by the Children and Social Work Act 2017.

This guidance sets out arrangements for undertaking child death reviews in Sussex. It should be read in conjunction and seen as complimentary with the following documents:

3. Scope and Purpose of this Protocol

This protocol aims to set out the processes to be followed when responding to, investigating, and reviewing the death of any Sussex child.

This includes the immediate actions that should be taken after a child’s death; the review of a child’s death by those who interacted with the child during life and any professionals involved in the investigation after death; through to the last stage of the child death review process which will be the statutory review arranged by the child death review partners by the Child Death Overview Panel (CDOP).

This guidance aims to clarify processes and sets out principles for how all organisations and professionals (e.g. Healthcare providers, Sussex Police, Local Authorities and ICB staff who care for children or have a role in the child death review process will work together to meet the below objectives:

- to ensure a thorough, balanced systematic and sensitive approach is undertaken to establish, as far as possible the cause(s) of the child’s death focusing on history, examination and investigations, and to identify any potential contributory factors;

- to ensure bereaved families are offered optimal support during a traumatic time, and that sensitivity is maintained alongside objectivity toward the cause/s of death;

- to ensure the safety, wellbeing and welfare of siblings, any other children associated with child, and subsequent children;

- multi-agency response and information sharing for the Child Death Review Process; maintain respectful professional curiosity and be aware of unconscious bias

- to preserve evidence;

- to identify and share learning.

All of these are of equal importance.

4. Terminology

Child

The child death review process covers children; a child is defined in the Act as a person under 18 years of age. A child death review must be carried out for all children regardless of the cause of death.

This includes the death of any live-born baby where a death certificate has been issued. In the event that the birth is not attended by a healthcare professional, child death review partners may carry out initial enquiries to determine whether or not the baby was born alive. If these enquiries determine that the baby was born alive the death must be reviewed.

For the avoidance of doubt, it does not include stillbirths, late foetal loss, or terminations of pregnancy (of any gestation) carried out within the law.

- stillbirth: baby born without signs of life after 24 weeks gestation;

- late foetal loss: where a pregnancy ends without signs of life before 24 weeks gestation.

Cases where there is a live birth after a planned termination of pregnancy carried out within the law are not subject to a child death review.

Child Death Review Partners

“Child death review partners” (“CDR partners”) are defined in section 16Q of the Children Act 2004 and means, in relation to a local authority area in England, the local authority and any ICB for an area any part of which falls within the local authority area. CDR partners for two or more local authority areas in England may agree that their areas should be treated as a single area. The responsibilities of CDR partners regarding the child death review process are set out in sections 16M-Q of the Children Act 2004. CDR Partners hold legal responsibility for ensuring that arrangements are made to review the death of a child who is normally resident within their local authority.

CDRM (Child Death Review Meeting)

The CDRM is a multi-professional meeting where all matters relating to an individual child’s death are discussed by professionals who were directly involved in the care of the child during their life, and any professionals involved in the investigation into their death. The nature of this meeting will vary according to the circumstances of the child’s death and the practitioners involved, and should not be limited to medical staff.

Child Death Overview Panels (CDOP)

Child Death Overview Panels (CDOP) is a multi-agency panel working on behalf of the CDR Partners to conduct the statutory review into the deaths of all live-born children normally resident within their area (from birth to 18 years of age). CDOPs identify factors in order to learn lessons and share any findings for the prevention of future deaths. CDOPs ensures independent, multi-agency scrutiny by senior representatives from key partner agencies (with no named responsibility for the child’s care during life) who together have expertise in a wide range of services regarding children’s health and wellbeing.

Designated doctor for child deaths

A senior paediatrician, appointed by the CDR partners, who will take a lead in coordinating responses and health input to the child death review process, across a specified locality or region.

Joint Agency Response

A coordinated multi-agency response (on-call health professional, police investigator, duty social worker), should be triggered if a child’s death:

- is or could be due to external causes;

- is sudden and there is no immediately apparent cause (including SUDI/C);

- occurs in custody, or where the child was detained under the Mental Health Act;

- where the initial circumstances raise any suspicions that the death may not have been natural; or

- in the case of a stillbirth where no healthcare professional was in attendance

Key Worker

A person who acts as a single point of contact for the bereaved family, who they can turn to for information on the child death review process, and who can signpost them to sources of support. This person will usually be a healthcare professional.

Lead health professional

When a Joint Agency Response is triggered, a lead health professional should be appointed, to coordinate the health response to that death. This person may be the senior attending paediatrician or senior nurse, with appropriate training and expertise. This person will ensure that all health responses are implemented, and be responsible for ongoing liaison with the police and other agencies.

Medical Certificate of Cause of Death (MCCD)

An official certificate that enables the deceased’s family to register the death, provides a permanent legal record of the fact of death, and enables the family to arrange the funeral. It provides information on the relative contributions of different diseases to mortality.

Medical Examiner

A medical examiner is a senior medical doctor who provides independent medical scrutiny of all non-coronial deaths, they have a responsibility to ensure:

The purpose of the medical examiner system is to:

- provide greater safeguards for the public by ensuring independent scrutiny of all non-coronial deaths

- Promote timely and appropriate referrals of deaths to the coroner

- provide a better service for the bereaved and an opportunity for them to raise any concerns to a doctor, or their appointed medical examiner officer, not involved in the care of the deceased

- improve the quality of death certification

- improve the quality of mortality data

- to ensure that possible clinical governance concerns have been highlighted at an early stage.

National Child Mortality Database

A National Child Mortality Database (NCMD) formed in April 2019 and collects child mortality data to enable more detailed strategic analysis and interpretation of the data arising from the completed Child Death Review process across England. All CDOP’s are required to submit copies of their analysis and data collected. The NCMD will ensure that child deaths are learned from and this learning is widely shared, both locally and nationally.

PSIRF

The Patient Safety Incident Response Framework (PSIRF) sets out the NHS’s approach to developing and maintaining effective systems and processes for responding to patient safety incidents for the purpose of learning and improving patient safety. The PSIRF will replace the current Serious Incident Framework (2015) which described the process and procedures to help ensure Serious Incidents are identified correctly, investigated thoroughly and, most importantly, learned from to prevent the likelihood of similar incidents happening again.

Perinatal Mortality Review Tool (PMRT)

The PMRT is a web-based tool that is designed to support a standardised review of care of perinatal deaths from 22+0 weeks gestation to 28 days after birth. It is also available to support the review of post-neonatal deaths where the baby dies in a neonatal unit after 28 days but has never left hospital following birth. At clinicians’ discretion it might also be used for the review of deaths of live-born infants.

Learning Disability Mortality Review (LeDeR) programme

LeDeR is a service improvement programme that reviews the deaths of people aged 4 years and over with a learning disability and autistic people. LeDeR works to:

- improve care for people with a learning disability and autistic people;

- reduce health inequalities for people with a learning disability and autistic people;

- prevent people with a learning disability and autistic people from early deaths;

- deaths of any child aged 4-17 yrs (inclusive) with a known learning disability, will be reviewed through the Child Death Review process.

Post Mortem

This is the medical term for ‘autopsy’. In most cases this will involve an examination by a specialist pathologist including opening of the body and head, collection of samples for ancillary investigations and microscopic examination of tissue samples. The results of all such investigations are usually required before a medical cause of death can be provided.

SUDI / SUDC (sudden unexpected death in infancy / childhood)

This encompasses all cases in which there is death (or collapse leading to death) of a child, which would not have been reasonably expected to occur 24 hours previously and in whom no pre-existing medical cause of death is apparent. This is a descriptive term used at the point of presentation, and will include those deaths for which a cause is ultimately found (‘explained SUDI/SUDC’) and those that remain unexplained following investigation.

- SUDI (Infants up to 24 months of age);

- SUDC (Death of child over 24 months of age).

SIDS (sudden infant death syndrome)

The sudden and unexpected death of an infant under twelve months of age, with onset of the lethal episode apparently occurring during normal sleep, which remains unexplained after a thorough investigation, including performance of a complete post-mortem examination and review of the circumstances of death and the clinical history. It is preferred as a registered cause of death to other equivalent terms such as ‘unascertained’ or ‘undetermined’. Labelling a death as SIDS does not exclude the possibility that the child may have died of a natural or external cause that we have been unable to ascertain or prove conclusively.

Unascertained

This is a legal term often used by coroners, pathologists and others involved with death investigation, where the medical cause of death has not been determined to the appropriate legal standard, which is usually the balance of probabilities.

IPD (Immediate Planning Discussion)

An IPD is a discussion held amongst the attending health professional and on-call police before the family leave the emergency department. They will consider outstanding investigations, notification of agencies, arrangements for the post mortem examination, and plans for a visit to the home or scene of collapse by those with appropriate forensic training.

IISPM (Initial Information Sharing and Planning Meeting)

The IISPM is a multi-agency meeting held following the death of a child (usually by the next working day) where a Joint Agency Response is required. This is jointly planned by the Senior Investigating Officer, Lead Health Professional and Children’s Social Care. Multi-agency professionals and specialist agencies that have been involved with the child/family will be requested to attend.

HSIB (Healthcare Safety Investigation Board)

HSIB is hosted by NHS England and NHS Improvement. HSIB is independent from regulatory bodies including the Care Quality Commission (CQC) and they investigate safety incidents without attributing blame or liability. The focus is to identify opportunities to learn and to improve patient safety across the system.

5. Operational Protocol

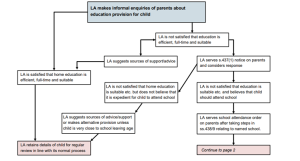

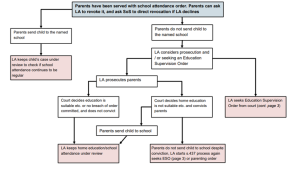

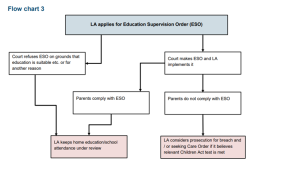

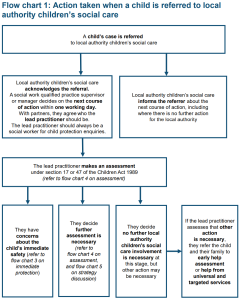

A child death review must be carried out for all children regardless of the cause of death. This Child Death Operational Protocol Flowchart (opens as a pdf) sets out the main stages of the process.

6. Immediate Decision Making and Notifications (All Deaths)

6.1 Immediate decision making discussion

In order to respond appropriately to each death, senior professionals attending the child at the end of their life should consult with appropriate professionals in order to determine the correct course of action. They should within 1-2 hours:

- identify the available facts about the circumstances of the child’s death;

- determine whether the death meets the criteria for a Joint Agency Response (JAR) – see Section 8, Joint Agency Response Protocol;

- determine whether the immediate and underlying cause(s) of death are understood;

- follow the agreed end of life care plan put in place by the lead health care professional during their life, unless concerns have been raised about the circumstances of their death;

- determine whether an issue relating to health care or service delivery has occurred or is suspected and therefore whether the death should be referred to the coroner and/or patient safety team for PSIRF investigation;

- identify how best to support the family;

- determine whether any actions are necessary to ensure the health and safety of others, including family or community members, healthcare patients and staff.

These discussions should be recorded in medical notes and the outcome of these discussions should also be fed back to the family. For template for this discussion, please see Appendix 3 of the Child Death Review Statutory and Operational Guidance (gov.uk).

If professionals become aware of a death or possible death from a relative or from an unusual source, please contact the CDOP team for discussion and confirmation.

7. Notifications

Within 24 hours of the death: a number of notifications must be made, this may vary depending on the circumstances of the death, age of child and the actions that must be taken.

The health care team should notify:

- General Practitioner (GP): to inform the child’s GP of the fact and circumstances of the death, so that the GP is able to support the family;

- Other professionals involved, as appropriate: midwives, health visiting, school nursing, acute and community medical teams, education, CCNs, social care, hospice;

- Child Health Information System (CHIS);

- The relevant CDR partners via their CDOP: through completion of a Notification Form via Sussex online eCDOP. Note: All professionals have a responsibility to notify their CDOP;

- MBRRACE / PMRT;

- Patient Safety / Clinical Governance;

- Medical Examiners: Medical Examiners should be notified and consulted for all non-coronial cases.

Medical examiners should follow national recommendations made within Good Practice Series: National Medical Examiner’s Good Practice Series No 6. – Child Deaths (Royal College of Pathologists) – opens as a pdf.

The Coroner: The Coroner must be informed at the earliest opportunity of any violent or unnatural death, or the cause of death is unknown, or the deceased died while in custody or otherwise in state detention. The Coroner should normally be contacted via the Coroner’s Officer. The Coroner has control of what happens to the child’s body and will decide if a post mortem examination is necessary.

Although the cause of death for most children can be understood, it has been agreed for child deaths occurring only in East Sussex, these should be discussed with the Coroner prior to a MCCD (death certificate) being signed.

If at any stage concerns are raised that abuse or neglect may have contributed to the infant/child’s death or significant concerns emerge about safeguarding issues, the senior Police officers, Head of Safeguarding or designated doctor for child death should be contacted for consideration of a Joint Agency Response. In these cases the police will normally take the lead in investigating the death. An initial multi-agency strategy discussion should be organised for any live siblings or children considered at risk.

After immediate decisions have been taken and relevant notifications made, a number of investigations may then follow. They will vary depending on the circumstances of the case and may run in parallel.

8. Joint Agency Response (JAR) Protocol

The Sudden Unexpected Death in Infancy and Childhood (PCP and RCPCH) – opens in pdf- gives comprehensive advice and expectations of all agencies involved in a JAR, and should be applied in full by all agencies. This protocol should be seen as complementary to the SUDI/C Guidelines.

The aims of the JAR are documented within the above guidelines however professionals should respond to meet the Sussex Child Death Review objectives which have been documented above.

A JAR should be triggered if a child’s death:

- is or could be due to external causes;

- is sudden and there is no immediately apparent cause (incl. Sudden Unexpected Death in Infancy/Childhood: SUDI/C);

- occurs in custody, or where the child was detained under the Mental Health Act;

- where the initial circumstances raise any suspicions that the death may not have been natural;

- in the case of a stillbirth where no healthcare professional was in attendance.

A Joint Agency Response should also be triggered if such children are brought to hospital near death, are successfully resuscitated, but are expected to die in the following days. In such circumstances the Joint Agency Response should be considered at the point of presentation and not at the moment of death, since this enables an accurate history of events to be taken, appropriate clinical investigations and, if necessary, a ‘scene of collapse’ visit to occur.

A Joint Agency Response should also be triggered where there is evidence that a child may be presumed dead. For example: A child being witnessed to have washed out to sea.

When a child with a known life limiting and or life-threatening condition dies in a manner or a time that was not anticipated, the lead health professional should liaise closely and promptly with a member of the medical, palliative or end of life care team who knows the child and family, to jointly determine how best to respond to that child’s death. If there are concerns that the death was premature or unusual this may trigger a JAR. Advice can be sought from the coroner or the designated doctor for child death/ CDR nurse team.

In these circumstances for a child with an End of Life Care Plan the arrangements may differ: For example, the coroner decides where the child’s body may be taken and this decision may be different to what was set out in the family’s prepared plan.

All deceased children that meet the criteria for a JAR should ideally be transferred to the nearest Children’s Emergency Department (ED) that will enable the JAR to be triggered and appropriate clinical investigations performed and hospital unexpected child death proforma completed.

However, deceased children (older than 12 years of age) that die in traumatic circumstances such as suspected/completed suicide, traumatic Motor Vehicle Accident / rail incidents with severely disrupted body can be transferred straight to the hospital mortuary from the scene/home. The agreement on where the deceased child will be transported, will be made between Coroners Officer, lead health professional and lead police investigator.

In any of these circumstances, the lead health professional, on-call police and social work team and the child death review nurse team (within working hours) should be contacted immediately to convene an Immediate Planning Discussion.

The Coroners’ officer should also be called and will attend ED. A discussion should take place with the on-call Consultant Paediatrician to plan the external examination and discuss what samples are required to be taken. If the child’s body has been transferred straight to the hospital mortuary from the scene/home the coroners’ officers will contact the on-call Consultant Paediatrician to consider and plan the external examination and discuss sampling.

This should include (as a minimum) the lead health professional, and lead police investigator and ideally take place before the family leave the emergency department (if applicable). Input from Children’s Services, the ambulance crew involved in the transfer to hospital and CDR nurse team is desirable. If these professionals are not able to attend a face to face discussion then their contribution may need to be virtual.

This Immediate Planning Discussion (IPD) should consider the factors listed in Section 8, Joint Agency Response Protocol, and also the following:

- any immediately available background information from health, police or social services and any concerns arising from this information;

- the safety and wellbeing of any other children in the household;

- Ensure that the coroners office is notified at the earliest opportunity;

- arrangements for the post-mortem examination, and plans for a visit to the home or scene of collapse by the lead police investigator and child death review specialist nurse / paediatrician;

- check that arrangements are in place for timely notification of all relevant agencies and professionals.

These discussions should be recorded in medical notes.

The Multi-Agency Safeguarding Hubs for Children (by area of residency) should be alerted as a matter of urgency so that the Joint Agency Response Initial Information Sharing and Planning Meeting (IISPM) can be arranged and chaired.

When responding to a child death who is resident outside of Sussex, the chairing of an IISPM may vary depending on their local child death procedures and on the circumstances of death. Professionals should liaise between children’s social care teams regarding planning of the IISPM. When a Sussex child dies out of area, the expectation is that the health professionals, police and senior social workers in that area will respond and liaise with local teams.

An Initial Information Sharing and Planning Meeting (IISPM) should be held as soon as possible after the death. This meeting:

- will be convened, chaired and minuted by Children’s Social Care (CSC);

- usually takes place on the next working day (during working hours) to ensure all relevant professionals can attend;

- may include a pre-meeting to discuss detailed accounts with medical staff and initial responders to discuss specific circumstances surrounding the death and clinical details that may not be appropriate for open discussions. A sanitised overview will be provided to all attendees of the IISPM this to reduce the risk of vicarious trauma;

- (as a minimum) should involve the lead health professional, lead police investigator, ambulance staff and child death review nurse;

- rhe designated doctors for child death and local CDOP Manager should be invited so that they are aware of the meeting;

- should include multi-agency professionals and specialist agencies that have been involved in the child’s life / knew the family. Some agencies may not have known the child in their life but will be involved in the investigation/review following the death;

- must invite a Public Health Consultant where the death is a suspected suicide;

- when is a child is suspected to have completed suicide, please ensure the NCMD JAR Checklist for suspected suicide is considered Joint Agency Response checklist for suspected suicide;

- within five working days, minutes of the meeting must be sent to the coroner, pathologist and the Pan-Sussex CDOP management team.

Where a child usually resident in Sussex, but has died out of local area, the local authority in which the child is usually resident is responsible for holding an IISPM. The local authority where the child has died will host the Strategy Discussion, and the local authority where the child is usually resident will contribute.

The purpose of the IISPM is:

- to share information currently available and obtain additional information from each agency’s service and knowledge of the child, family and others involved. In particular:

- events leading to and the circumstances of the child’s death;

- healthcare provided to the child including medical intervention;

- the physical environment (including home or scene of death information);

- previous or ongoing child protection or safeguarding concerns;

- previous unexplained or unusual deaths in the family;

- lived experience of the child;

- parental capacity including emotional and physical concerns;

- possible or confirmed medical conditions within the immediate family;

- service issues / failures / concerns;

- social media usage of the child;

- consider the possible cause/s of death;

- plan future care and support of the family, including who will provide the family with bereavement support;

- consider the needs of siblings and other children in the household;

- identify support for the child’s immediate and extended peer groups and professionals;

- consider triggering a contagion for suspected suicide;

- identify any immediate and urgent learning to be shared;

- enable consideration of any child protection risks to siblings/any other children living in the household and to consider the need for child protection procedures and any other action (Section 47 enquiries);

- agree whether a follow-up meeting should be held (usually after the preliminary post mortem results is available and permission to share the result has been given by the coroner);

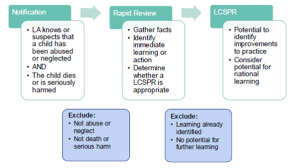

- agree whether a referral should be made to the child safeguarding partnerships for consideration of a rapid review. It may be more appropriate to convene a short meeting after the IISPM with a few key (CSC, Designated Doctor/nurse, Police) to decide if the criteria are met. In most cases it will be more appropriate to await the outcome of the full medical examination, results and post mortem examination (provisional or completed);

- identify any other actions or investigations that may be necessary;

- to consider whether a communication strategy is required;

- agree agency responsible for convening the CDRM.

If JAR professionals identify safeguarding risk/s, further information is needed or emerging information that needs to be discussed, CSC should arrange a Follow up Initial Information Sharing and Planning Meeting. This should include the lead health professional (paediatrician), child death review specialist nurse, police investigator and coroner’s officer to:

- review any emerging information including preliminary PM results, outcome of the joint visit (if undertaken), results of any other investigations;

- consider what is known about the cause of death and any possible contributory factors;

- determine whether any further investigations or enquiries are required, including the need for a forensic post-mortem;

- confirm what information can be provided to the family, how this will be shared, and by whom;

- consider whether a referral to the Partnership’s Child Safeguarding Practice Review Group is required.

The information shared at both the IISPM and follow-up meetings (including the minutes) are strictly confidential and should only be shared on a need to know basis. This information must not be shared outside of attendees organisation without prior consent from the chair or CDR Partnership (LA and ICB). The minutes should be stored in line with organisations Data Protection and Confidentiality procedures.

In circumstances where a child has died, and abuse or neglect is known or suspected to have caused or directly contributed to the death, professionals at the initial information-sharing and planning meeting should notify the safeguarding partners. They have the responsibility to determine whether the case meets the criteria for a local child safeguarding practice review. (it is important to be aware that this referral can occur at any part of the child death review process).

Professionals should refer to Child Safeguarding Practice Review Panel guidance (gov.uk) or contact the relevant Head of Safeguarding.

8.1 Responsibility for deciding whether to notify

Where an agency other than the local authority becomes aware of an incident that appears to meet the criteria for notification to the National Panel, they should discuss this with their local authority counterparts to reach an agreement on whether or not to notify. There may be instances where safeguarding partners do not initially agree on whether there is a need to notify the National Panel following a serious incident. For instance, it may be unclear whether an incident appears to have met the criteria for notification, although we hope this guidance provides further help. Discussion between safeguarding partners about cases and the decision to notify is crucial. Strong partnership working is predicated on collaboration and open dialogue. Where agreement cannot be reached through dialogue between the safeguarding partners alone, we encourage using the support of appointed independent scrutineers to help resolve differences. Ultimately however, the final decision on whether or not to submit a notification to the Panel following an incident is the responsibility of the local authority. Should a child death review partner consider at any time during the CDR process that a referral should be made they should present their rationale to the relevant Head of Safeguarding and Designated Doctor in their capacity as Statutory leads of the CDR process. This approaches also utilises their professional expertise as members of the Case Review Group.

The Local Authority must also notify Secretary of State and Ofsted where a child looked after has died, whether or not abuse or neglect is known or suspected.

9. Suspected Suicide

A child suspected suicide should always follow the Joint Agency Response process and professionals should also follow the procedure in Response to a suspected suicide chapter.

LA areas should follow their guidance to managing suicide especially in educational settings.

9.1 Initial action at the scene

Ambulance staff:

The ambulance service Emergency Operations Centre will immediately notify the police control room when there is a call to the scene of an unexpected child death.

The recording of the initial call to the ambulance service should be retained in case it is required for evidential purposes.

Ambulance staff should follow the Joint Royal Colleges Ambulance Liaison Committee Guidelines and the South East Coast Ambulance Service Safeguarding Procedures. In summary:

-

- do not automatically assume that death has occurred, clear the airway and if in any doubt about death apply full cardiopulmonary resuscitation;

- transport the child to an accident and emergency department *;

- inform the accident and emergency department giving estimated time of arrival and patient’s condition;

- record how the body was found – including the position of the child (e.g. prone) clothing worn and the reported circumstances;

- note any comments made by the carers, any background information given, any evidence of possible substance misuse and the conditions of the living accommodation;

- pass on all relevant information to the accident and emergency department receiving doctor and to the police.

Any suspicions should be reported directly to the police and the receiving doctor at the hospital as soon as possible.

*All children who suffer cardiac and respiratory arrest must be taken to hospital, this will not be a difficult decision on most occasions as the child or baby will be actively resuscitated. However, there are some occasions, although extremely rare, when the decision is made not to resuscitate, historically these cases have been left at home, it is vital that now, even these cases are transported to hospital. This does not mean that resuscitation should be undertaken just to facilitate transport.

The reason for this is to enable the process for investigating the cause of death to start as soon as possible after the event. It has been shown that cell and tissue deterioration occurs extremely quickly in children and this can have a dramatic effect on whether a definitive cause of death can be found. This, of course, must be dealt with as sensitively as possible.

In these circumstances the crew should:

- explain fully the reason for transport to hospital to the parents;

- inform the receiving hospital via a pre-alert through the Emergency Operations Centre (EOC) before leaving scene. EOC should make arrangements with the paediatrician on duty to meet the family, usually within the A&E department;

- update the police regarding the movement of the patient if they are not already present. Parents have the right to find out what has caused their child to die and getting the investigation underway as soon as possible will give them the best chance of getting that answer;

- parents have the right to find out what has caused their child to die and getting the investigation underway as soon as possible will give them the best chance of getting that answer.

The only exceptions to the above would be when the death has occurred following planned end of life or palliative care, or when the cause of death is very obvious such as in the case of severe trauma. Under these circumstances transfer to local mortuaries (under the direction of the police, coroners officer and consultant paediatrician) or leaving the patient at home will remain the appropriate course of action.

Police staff:

The provision of medical assistance to the child is obviously the first priority. If an ambulance is not present ensure one is called immediately and consider attempting to revive the child unless it is absolutely clear that the child has been dead for some time. Ensure that the Detective Inspector (DI)/Detective Sergeant (DS) is informed of any resuscitation attempts in order that they can inform the pathologist.

The first officer at the scene must make a visual check of the child and his/her surroundings, noting any obvious signs of injury. Handle the child as if he or she were alive; ascertain and use the child’s name whenever referring to the child.

Normally the first officer attending the scene will be responding to an emergency call relating to a child’s death. This officer will assume control of the situation being mindful of the sensitivity of the situation and ensure that the following specialist officers are contacted and attend:

- a detective inspector (DI) must be contacted to take charge of the investigation and attend the scene. Where available this will be a DI who has received training in Investigating Sudden Childhood Death. This will not apply in incidents where the death is as a result of a road traffic collision (RTC). In these cases the duty senior investigating officer (SIO) arrangements for the investigation of Road Traffic Collisions (RTC) will apply.

The DI attending the scene of the death will:

- assess and appropriately preserve the scene;

- decide what level of investigation is necessary;

- if at any stage the inquiry indicates that the death is suspicious then a Force Senior Investigating Officer (SIO) must be contacted immediately;

- consider the need for seizure of exhibits and any photography/video recording;

- discuss with the Coroner’s officer/Coroner and paediatrician of the need to undertake a skeletal survey prior to the PM, and if authorised arrange in consultation with the consultant paediatrician. Arrangements will vary between Coroner’s areas;

- confirm with the Ambulance Service where the child will be taken depending on the circumstances;

- where the death is initially unexplained, ensure the child is examined at the hospital by a consultant paediatrician;

- ensure the attendance of an appropriate police officer at the PM to fully brief the pathologist;

- notify circumstances of death to local CDOP in cases where a child is not taken to A&E but goes direct to a mortuary

A Detective Sergeant, or if unavailable a Detective Constable, from the relevant Safeguarding Investigations Unit should attend in support of the Lead investigator. When Safeguarding Investigations Unit officers are not on duty the Divisional Duty DS or DC should attend the scene but hand over any enquiries to the Safeguarding Investigations Unit at the earliest opportunity. They will:

- act as a source of advice on child protection matters to the DI;

- consider any apparent child protection issues at the scene;

- consider the needs of any siblings;

- undertake enquiries at the direction of the DI;

- discuss and if appropriate arrange a joint home visit with a consultant paediatrician or CDR Specialist Nurse;

- inform the Coroner’s Officer;

- initiate immediate planning discussion;

- ensure in liaison with the paediatrician that all medical records and a copy of the pathologist’s enquiry form are made available at the PM;

- request and retain the relevant personal child health record form the parents and provide copies to health professionals when requested.

9.2 The scene

Role of the Police:

The preservation of the scene and the level of investigation will be relevant and appropriate to the presenting factors. This must be done sensitively and where possible avoiding wearing uniform.

Officers initially attending the scene should ensure it is preserved until the DI attends. Any relevant items should be drawn to their attention, but the DI will decide what items will be retained and removed from the scene.

Consideration should be given to:

- commencing a scene log;

- photographs / video of the scene;

- only retain bedding if there are obvious signs of forensic value such as blood, vomit or other residues. The routine collection of bedding is neither necessary for any investigative purpose, nor appropriate for the family;

- retain items such as the child’s used bottles, cups, food or medication;

- the child’s nappy and clothing should remain on the child but arrangements should be made for them to be retained at the hospital. If the nappy has already been removed from the baby prior to police arrival ensure that it is recovered from the parents and handed to the paediatrician at the hospital for possible laboratory investigation. There is no need to retain any other clothing unless the baby’s clothes have been changed prior to the arrival of the police;

- records from the ambulance monitoring equipment which may be of evidential value; it is possible this information may only be retained for 24 hours.

The above is NOT an exhaustive list of considerations and should be treated only as a guide. They will not be necessary in every case. Refer to Appendix 3: Factors which may Arouse Suspicion.

If it is necessary to remove items from the house, do so with consideration for the parents. Explain that it may help to find out why their child has died. Ask the parents if they want the items returned.

Record any environmental features which may indicate neglect or could have contributed to the death such as temperature of scene, condition of accommodation, general hygiene and the availability of food / drink.

At home, unless the death is clearly unnatural, there is no reason why parents cannot hold their dead child. This should however take place under the discreet observation of a police officer.

9.3 At the hospital

Hospital staff

Appropriate clinical investigations (commonly referred to as the Kennedy samples) should be performed in some cases. The focus for the Kennedy guidance is on children aged 0–24 months, but in order to be consistent with Working Together, which covers all children aged 0–18 years, it is suggested that these principles may apply to children of all ages, although there will be exceptions. The decision whether to take Kenedy samples should be made by the lead paediatrician, in discussion with the DI and/or Coroner/coroner’s officer.

It is unlikely that skeletal surveys will be completed out of hours.

The paediatrician should endeavour to examine the. child’s (particularly infants) eyes with an ophthalmoscope, however the findings of this merely guide the ‘investigation’ and cannot be used as evidence in legal proceedings. If there are concerns there may be traumatic injuries to the eyes (retinal haemorrhages etc – (a retinal haemorrhage is bleeding from the blood vessels in the retina at the back of the eye)) the Police will need to arrange a forensic post-mortem examination.

Certain factors in the history or examination of the child may give rise to concerns about the circumstances of death. If such factors are identified, they should be documented and shared with the coroner, Police and professionals in other key agencies. All injuries should be recorded and the lead police investigator should arrange a photographic record.

- Ensure that the child is taken to the appropriate area of the Accident and Emergency Department even if they appear to have been dead for some time. The child should not be taken straight to the mortuary. (See Bodies of Children under 12 yrs of age (unexpected deaths) for exceptions to this e.g. children > 12 years who have died as a result of trauma).

- Call the duty consultant paediatrician and the resuscitation team. Find out the identity of the people with the child and their relationship to the child. Use the child’s first name.

- Allocate a nurse to look after the family to keep them informed about what is happening. The nurse should record any medical or other information they obtain.

- A detailed history and examination are extremely important in the process of trying to identify the cause of death.

- A paediatrician should record a detailed verbatim history of events leading up to the death, past and recent symptoms, any resuscitation attempts at home and any family history of childhood deaths or serious illness.

- A full examination should be undertaken by a paediatrician and a careful record of any findings made on a body chart, including:

- the child’s general appearance, cleanliness, any blood or secretions around nose or on clothes;

- marks on skin, bruises, abrasions, other injuries, skin conditions;

- marks from invasive procedures or resuscitation attempts such as venepuncture, cardiac puncture or cardiac massage;

- lesions inside the mouth including frenulum/frenum and identifying possible effects of intubation;

- appearance of retinae, although these may not be clearly seen;

- any signs of injury to the genitalia or anus.

Traumatic deaths (over 12ys):

- Visual external examination of the body should take place with Paediatrician, Coroner’s officer and Police Lead Investigator – unless the body is significantly disrupted (in cases such as death on railway)

- Blood and urine samples (especially toxicology) should always be considered. The remaining Kennedy samples are not normally necessary in these cases. Any disagreement should be referred to the Coroner.

- Vitreous humour samples may be taken by hospital mortuary technicians if required.

Bodies of Children under 12 yrs of age (unexpected deaths):

- Visual external examination of the body should take place with Consultant Paediatrician, Coroner’s officer and Police Lead Investigator. In some cases it will not be necessary for a paediatrician to conduct this (lead paediatrician to discuss with the DI and Coroner).

- Clinical judgement should be applied when considering the taking of the Kennedy samples (if there is no apparent cause of death then a full set should be attempted). A discussion should take place between the consultant Paediatrician/Coroner’s Officer and Police Lead Investigator. Any disagreement should be referred to the Coroner.

- Blood and urine samples should always be attempted.

- Vitreous humour samples may be taken subsequently by hospital mortuary technicians.

9.4 Assessment of the environment and circumstances of the death (joint home / scene visit)

As soon as possible and when relevant, after the infant/child death, the lead paediatrician or CDR specialist nurse (this should be considered at the IISPM) and police investigator should jointly visit the family at home or at the site of the infant/children collapse or death. Prior to the visit, the lead paediatrician and/or CDR specialist nurse with the police investigator should inform the family of the nature and purpose of this home visit.

The purpose of this visit is to obtain more detailed information about the circumstances of the death, assess the environment in which the infant/child died (or collapsed) and to provide the family with information and support.

This visit should normally take place within daylight hours, after the IISPM, and within 24 – 48 hours of the death. If there is likely to be a delay in arranging the joint visit, the police investigator should consider whether the police should carry out an initial visit to review the environment, ascertain whether there are any forensic requirements and appropriately record what is found. Unless there are clear forensic reasons to do so, the environment within which the infant died should be left undisturbed so that it can be fully assessed jointly by the police and health professional, in the presence of the family. CDR Nurse or paediatrician should consider the sleep environment, including temperature of the room, bedding, ventilation, smoke and other hazards etc.

Professionals should ensure adequate time is allocated for the visit and to allow for the family to go at their own pace, respecting that they may find it difficult to talk through the events or go into the room where the infant has died. It is likely that family friends or grandparents may be present to support the parents, and this should be respected.

The initial history should be reviewed at the home visit with the family to ensure that all information is accurately captured and any points that were unclear or missing clarified.

Particular note should be made of any observations made by the family in the days before the infant’s death. They may have taken photographs or video clips on a mobile phone that could shed light on the child’s health or condition before death.

Consideration should be given to reconstruction of the sleeping environment, for example, with the use of a doll or prop. There is no strong evidence that this provides a more accurate understanding of the mode or circumstances of death, but it may prove helpful, particularly if the account is not clear, or if there are indications of possible overlaying or asphyxiation. At all times care should be taken not to further distress the family if a reconstruction is required.

The police lead investigator should consider whether to request crime scene investigators to take photographs or a video of the scene of the infant’s death, and whether any items should be seized for further forensic investigation. Other possible relevant recordings, such as room temperature, are detailed within the police-approved professional practice guidance for investigators.

It is rarely necessary to seize bedding or clothing and these rarely add anything to the investigation. However, there may be circumstances when an infant’s cot or other sleeping environment needs to be taken for further examination. This should only be taken after the joint visit, so all items can be seen first in situ. Similarly, there may be circumstances where an infant’s feeding bottle or other feeds or medications need to be taken for further analysis.

The family should be informed of the further investigations that will need to be carried out, including the post-mortem examination, and how and when they will be informed of the results.

The CDR specialist nurse should share bereavement resources from the Lullaby Trust, to help parents, families, and carers understand and navigate the child death review process. This document should be offered, in a printed format, to all bereaved families and/or carers. The family should be informed that the CDR specialist nurse will act as their point of contact for support or advice and also, given contact details for local bereavement support and relevant local or national organisations.

Following a review of all the information gathered a report of the initial findings, including details of the history, initial examination of the infant and findings from the home visit, as well as an account of any medical investigations and procedures carried out should be prepared by the paediatrician or CDR specialist nurse. This may be done using a proforma, should be completed as a matter of urgency.

This report should be made available to the pathologist, the coroner, the police investigator and local CDOP as soon as possible, and prior to the post-mortem examination to inform the pathologist.

10. Investigation and Information Gathering

After the immediate decisions and notifications have been made, a number of investigations may then follow. Which investigations are necessary will vary depending on the circumstances of the individual case. They may run in parallel, and timeframes will vary greatly from case to case. These may include:

The learning from these investigations and concurrent processes may inform the CDRM and must be available for the anonymous independent review by CDR partners at CDOP.

Staff from all agencies need to understand that on occasions in suspicious circumstances (please see 11.1.139 – ‘Factors that arise suspicion’) the early arrest of parents or carers may be essential in order to secure and preserve evidence and to facilitate the investigation. Professionals need to be aware that they may be required to provide statements of evidence in these circumstances.

Essential information such as demographic data, detailed information relating to the circumstances of death with consideration of the medical and social history, the physical environment and any service delivery issues for the child and family must be gathered for all child deaths. Agencies or professionals who have information relevant to a child death will be requested by the CDOP to complete a Reporting Form.

11. Post Mortem Examination (Coronial)

The aim of the post mortem examination is to establish, as far as is possible, the cause of death. This investigation will concentrate not just on the infant, but will consider the family history, past events and the circumstances. These factors can be helpful in determining why an infant died. All parts of the process should be conducted with sensitivity, discretion and respect for the family and the infant who has died

When the death has been reported to the coroner, depending on the circumstances of the death, a PM may be requested, which will be carried out by a paediatric pathologist (or in specific circumstances, an adult pathologist or home office forensic pathologist). The coroner is required by law to order a post-mortem when a death is suspicious, sudden or unnatural, consent will not be asked by the family for this to take place.

Prior to commencing the examination, the pathologist should be fully briefed on the history and physical findings at presentation, and on the findings of the death scene investigation by the lead health professional, Specialist CDR Nurse and police investigator. Other photographs of the infant that may have been taken at presentation or in the emergency department should also be made available.

If significant concerns have been raised about the possibility of neglect or abuse having contributed to the infant/child’s death, a forensic pathologist should accompany the paediatric pathologist and a joint post-mortem examination protocol should be followed.

Families have the right to be represented at the PM by a medical practitioner of their choice, provided they have notified the coroner of their wishes. The final decision rests with the Coroner.

The coroner should be immediately informed of the initial results of the PM, which may also, with the coroner’s permission, be discussed with the lead health professional and lead police investigator as required.

Once the initial results of the post mortem (or provisional results) are known the lead health professional should be informed and an interim/review discussion or consideration of a follow up IISPM should take place.

These discussions may take the form of telephone discussions. However where the circumstances are complex or there are many professionals involved a further multi-agency meeting(s) may be required.

The lead health professional and the police investigator (where appropriate) should, with the coroner’s permission, arrange to meet the family to discuss the initial findings. It is important at that stage to emphasise that the findings are preliminary, that further investigations may be required, and that it is not possible, at that stage, to draw any conclusions about the cause of death. The family must be kept up to date as results come back and the lead health professional should offer to meet with the parents once the final PM report is completed. Parents MUST NOT receive a PM report directly, this can be traumatic for them and requires careful direct communication; the paediatrician’s role is to help the family understand the findings of the post mortem.

As part of the explanation about the PM examination given to the family, the coroner’s officer must explain that, according to the Coroners (Investigation) Regulations 2013, tissue samples will be taken and that, following the coroner’s investigation, the family can determine the fate of the tissue according to the Human Tissue Act 2004.

12. Post Mortem Examination (Non-Coronial):

Hospital Post-mortems are sometimes offered to families and will be requested by doctors. This could provide more information about an illness or the cause of death, or to further medical research. Hospital post-mortems can only be carried out, with consent.

If a hospital post-mortem was requested, the results should be sent to the referring hospital and results discussed with the family. If the PM brings new information to light to the referring hospital that brings the cause of death on the MCCD into question, this should be discussed with the coroner, paediatrician and medical examiner.

13. NHS Serious Incident Investigation

Serious incident investigations are undertaken with the sole aim of learning about any problems in the delivery of healthcare services and in understanding the causes and contributory factors of those problems of which there may be several. Awareness that a serious incident may have occurred may come sometime after the child’s death. It is never too late to instigate a serious incident investigation. Serious incident investigations may occur in parallel to other investigations e.g. a Joint Agency Response.

NHS serious incident investigations are not conducted to hold organisations or individuals to account. They are designed to generate information that can be used to implement effective and sustainable changes to care provision, to reduce the risks of similar problems occurring in the future.

NHS trusts use the Serious Incident Framework (2015) to guide their investigation of serious incidents however in future will transition to an updated Patient Safety Incident Response Framework (PSIRF).

14. The Healthcare Safety Investigations Branch (HSIB)

Healthcare Safety Investigations Branch (HSIB) carries out independent investigations into safety concerns that occurred after 1 April 2017, within NHS funded care in England. Its objective is to be thorough, independent and impartial in its approach without apportioning blame or liability. The HSIB accepts referrals from any source, and these can be made through the HSIB website. The investigations that are taken forward are chosen due to their potential to achieve system-wide learning and improvement, and ultimately to improve the care provided for patients. This is accomplished by working collaboratively with all involved in the incident, including patients and families, to establish cause and make recommendations that enable system-wide change.

Separately, HSIB investigate NHS Serious Incident Investigation cases of intrapartum stillbirth, early neonatal deaths and severe brain injuries from 37 weeks gestation. These investigations will continue to be characterised by a focus on learning and not attributing blame, and the involvement of the family is a key priority, but will not be covered by the safe space principles unlike their national investigations into broader safety concerns.

15. Family Engagement and Bereavement Support

As stated, it is important for every family to have their child’s death sensitively reviewed in order to, where possible, identify the cause of death and to ensure that lessons are learnt that may prevent further children’s deaths. All parents and carers should be informed about the child death review process and are given the opportunity to contribute to investigations, meetings and be advised of their outcomes.

All staff in all agencies and organisations have a duty to support bereaved parents and carers after their child’s death and to show kindness and compassion. It should be remembered that bereaved parents may be in state of extreme shock when their child has died.

Where there have been issues with the quality of care provided, healthcare organisations have a duty of candour to explain what has happened, to apologise as appropriate, and to identify what lessons may be learnt to reduce the likelihood of the same incident happening again. This provision should extend beyond the medical sector to any instances of error in the care of the child.

Each child death is unique, therefore the support around the family is individual to the family and the circumstances of the child’s death. The family/carers may receive support from different services as the processes that follow the death of a child can be complex, in particular when multiple investigations are required. Recognising this, all bereaved families should be given a ’keyworker’ to whom they can provide information on the child death review process, the course of any investigations pertaining to the child, including liaising with the coroner’s officer and any police family liaison officer and who can signpost them to sources of support.

When a child death triggers a JAR, the keyworker will usually be the CDR specialist nurse and this should be confirmed at the IISPM.

In the case of an explained death, the keyworker is likely to be a member of the CDR nurse team or an appropriate health professional. For all deaths, families should be able to contact their keyworker during normal working hours.

An appropriate consultant neonatologist or paediatrician should also be identified after every child’s death to support the family. This might either be the doctor that the family had most involvement with while the child was alive or the designated professional on-duty at the time of death. The keyworker where appropriate, will liaise with the allocated doctor to arrange necessary follow-up meetings at locations and times convenient to the family.

At the time of a child’s death, other professionals may also provide vital support to the family; these include (but are not limited to) the GP, clinical psychologist, social worker, family support worker, midwife, hospice, community nurse, health visitor or school nurse, palliative care team, chaplaincy and pastoral support team.

Parents should be informed by their key worker/CDR nurse, that the review at CDOP will happen, and the purpose of the meeting should be explained. Particular care and compassion is needed when informing parents about the meeting and its purpose, to avoid adding to parents’ distress or giving the impression in error that the parents are being excluded from a meeting about their child. With this in mind, it should be made clear that the meeting discusses many cases, and that all identifiable information relating to an individual child, family or carers, and professionals involved is redacted.

It should also be explained to parents that because of the anonymous nature of the CDOP review, it will not be possible to give them case specific feedback afterwards.

Parents should be assured that any information concerning their child’s death which they believe might inform the CDOP review would be welcome and can be submitted to the CDOP Management team.

16. Child Death Review Meetings for All Deaths

The CDRM is a multi-professional meeting where all matters relating to an individual child’s death are discussed by the professionals directly involved in the care of that child during life and their investigation after death.

In all cases, the aims of the CDRM are to:

- review the background history, treatment, and outcomes of investigations, to determine, as far as is possible, the likely cause of death;

- ascertain contributory and modifiable factors across domains specific to the child, the social and physical environment, and service delivery;

- describe any learning arising from the death and, where appropriate, to identify any actions that should be taken by any of the organisations involved to improve the safety or welfare of children or the child death review process;

- review the support provided to the family and to ensure that the family are provided with the outcomes of any investigation into their child’s death; a plain English explanation of why their child died (accepting that sometimes this is not possible even after investigations have been undertaken) and any learning from the review meeting;

- ensure that CDOP and, where appropriate, the coroner is informed of the outcomes of any investigation into the child’s death; and

- review the support provided to staff involved in the care of the child.

For deaths of babies in a midwifery unit, on delivery suite, and in a neonatal intensive care unit, the child death review meeting will often be known as a perinatal mortality review group meeting. This meeting is supported by the use of the national Perinatal Mortality Review Tool (PMRT) and advice and support about the use of the tool is provided by the MBRRACE-UK / PMRT Team.

The CDRM is a professionals-only meeting chaired by a suitable lead professional within the organisation where the death was declared. In order to allow full candour among those attending, and so that any difficult issues relating to the care of the child can be discussed without fear of misunderstanding, parents should not attend this meeting. However, parents /carers should be informed of the meeting by their keyworker and have an opportunity to contribute information and questions through their keyworker if the family choose to engage with the child death review process.

The CDRM is usually arranged by the organisation which confirms the death of the child and considered an integral part of wider clinical governance processes. The organisation of the meeting might be informed by practical considerations relating to where the majority of the child’s treatment took place.

In exceptional cases where the deceased child / young person has not been taken to the hospital, the most relevant agency/service should lead on and arrange the CDRM.

The meeting should take place once investigations (e.g. any NHS serious incident investigation or post-mortem examination) have concluded, and reports from key agencies and professionals unable to attend the meeting have been received.

The meeting should take place as soon as is practically possible, ideally within three months, although serious incident investigations and the length of time it takes to receive the final post-mortem report may cause delay.

The meeting should not take longer than 1-2 hours maximum. It is not necessary for each representative to share a full chronology of their service’s role in the child’s life as this will add significant time to the meeting. A brief summary or report by exception may be sufficient in most cases. This means the focus of the meeting can be on support for the family and identifying the learning and modifiable factors.

Each child’s death requires unique consideration and where possible, should engage professionals across the pathway of care. Invitees to the CDRM should be established and quoracy (for key professionals) determined by chair prior to invites. If professionals are unable to attend, they may be required to submit a report to the meeting.

The CDRM should ensure that a LeDeR programme representative is represented at the meeting when a child or young person aged 4-17 years who has learning disabilities is reviewed.

The CDRM organisers should alert the CDOP management team of the date of their CDRM and the Chair for the meeting.

To support the chairs with their Child Death Review Meeting preparation and developing a broad understanding of the case, the CDOP management team can advise where possible with coordination and provide information that has been gathered e.g. consolidated agency reporting forms. This should be managed with strict confidentiality, and not distributed to any other parties, including CDRM attendees, or permanently stored to any external systems other than the information shared should be securely destroyed / removed following the meeting.

The CDRM may proceed in the context of a criminal investigation, or prosecution, in consultation with the senior investigating police officer. The meeting cannot take place if the criminal investigation is directed at professionals involved in the care of the child, when prior group discussion might prejudice testimony in court. In these cases, discussions should take place with police with a view to seeking agreement to hold a modified CDRM to ensure family support needs are addressed.

The CDRM should take place before the coroner’s inquest to inform and contribute to the coroner’s investigation.

When reviewing a death where abuse or neglect is known or suspected to have caused or contributed to the death, professionals at the meeting should notify the safeguarding partners. They have the responsibility to determine whether the case meets the criteria for a local child safeguarding practice review. Professionals should refer to the Child Safeguarding Practice Review Panel Guidance (gov.uk) or contact the relevant Head of Safeguarding.

At the meeting’s conclusion, there should be a clear description of what follow- up meetings have already occurred with the parents, and who is responsible for reporting the meeting’s conclusions to the family. This would generally be the CDR nurse who is supporting the family. In a coroner’s investigation, such liaison should take place in conjunction with the coroner’s office, bearing in mind that the conclusion on the cause of death in such cases is the responsibility of the coroner at inquest.

Outputs from CDRMs (including a draft Analysis Form) should be circulated to attendees and shared with the Child Death Overview Panel and HM Coroner (if this is applicable and under coronial investigation) within 4 weeks of the meeting.

The information shared at the CDRM and the minutes are strictly confidential and should only be shared on a need to know basis. This information must not be shared outside of attendees organisation without prior consent from the chair or CDR Partnership (LA and ICB). The minutes should be stored in line with organisations Data Protection and Confidentiality procedures.

Actions arising from CDRMs should be captured within a formal action tracker and completion monitored and followed up through internal assurance processes. Local learning from CDRM’s should feed into the organisations learning from deaths governance.

17. Child Death Overview Panel

CDOP is a multi-agency panel set up by CDR partners to review the deaths of all children normally resident in Sussex, and, if appropriate and agreed between CDR partners, the deaths in their area of non-resident children, in order to learn lessons and share any findings for the prevention of future deaths.

CDOPs should conduct an anonymised secondary review of each death where the identifying details of the child and treating professionals are redacted.

The CDOP ensures independent, multi-agency scrutiny by senior professionals with no named responsibility for the child’s care during life. The review will occur once all other child death processes i.e. coronial inquest or Child Safeguarding Practice Review have been completed.

The general and themed panels are not quorate without a Designated Doctor for Child Deaths (not mandatory for the neonatal panel).

The functions of CDOP include to:

- collect and collate information about each child death, seeking relevant information from professionals and, where appropriate, family members;

- analyse the information obtained, including the report from the CDRM, in order to confirm or clarify the cause of death, to determine any contributory factors, and to identify learning arising from the child death review process that may prevent future child deaths;

- make recommendations to all relevant organisations where actions have been identified which may prevent future child deaths or promote the health, safety and wellbeing of children;

- notify the Child Safeguarding Practice Review Panel and local Safeguarding Partners when it suspects that a child may have been abused or neglected;

- notify the Medical Examiner (once introduced) and the doctor who certified the cause of death, if it identifies any errors or deficiencies in an individual child’s registered cause of death. Any correction to the child’s cause of death would only be made following an application for a formal correction;

- provide specified data to the NCMD via eCDOP;

- produce an annual report for CDR partners on local patterns and trends in child deaths, any lessons learnt and actions taken, and the effectiveness of the wider child death review process; and

- contribute to local, regional and national initiatives to improve learning from child death reviews, including, where appropriate, approved research carried out within the requirements of data protection

The panel membership of CDOP includes professionals from a range of agencies with safeguarding expertise including professionals who are also members of the Local Safeguarding Children Partnership Case Review Groups. CDOP is therefore well placed to consider abuse and neglect when reviewing child deaths and to refer onto the Local Safeguarding Children Partnerships where consideration by the Case Review Group of undertaking a Rapid Review or LCSPR is indicated in line with national guidance.

CDOP, on behalf of CDR partners, may request any professional or organisation to provide relevant information to it, or to any other person or body, for the purposes of enabling or assisting the performance of the child death review partner’s functions. Professionals and organisations must comply with such requests.

CDOP should aim to review all children’s deaths within six weeks of receiving the report from the CDRM or the result of the coroner’s inquest. The exception to this might be when discussion of the case at a themed panel is planned.

CDOP should assure itself that the information provided to the panel provides evidence that the needs of the family, in terms of follow up and bereavement support, have been met.

Sussex CDOP should record the outcome of their discussions on a final Analysis Form, and submit copies of all completed forms associated with the child death review process and the analysis of information about the deaths reviewed (including but not limited to the Notification Form, the Reporting Form, Supplementary Reporting Forms and the Analysis Form) to the NCMD.

Some child deaths will be best reviewed at a themed meeting. A themed meeting is one where the Sussex CDOP, or with neighbouring CDOPs, will collectively review child deaths from a particular cause or group of causes. Such arrangements allow appropriate professional experts to be present at the panel to inform discussions, and/or allow easier identification of themes when the number of deaths from a particular cause is small.

The CDOP should ensure that a LeDeR programme representative is represented at the panel when a child or young person aged 4-17 years who has learning disabilities is reviewed.

Appendix 1: JAR Checklist for Suspected Suicide in Children and Young People (CYP)

Click here to view Joint Agency Response Checklist for Suspected Suicide in Children and Young People

Appendix 2: General Advice for Professionals when Dealing with a Family, following an Unexpected Death

- This is a very difficult time for everyone. The time spent with the family may be brief but events and words used can greatly influence how the family deals with their bereavement in the long term. It is essential to maintain a sympathetic and supportive attitude, whilst objectively and professionally seeking to identify the cause of death.

- Remember that people are in the first stages of grief. They are likely to be shocked and may appear numb, withdrawn, angry or very emotional.

- The child should always be referred to and handled as if they were still alive and their name used throughout.

- Professionals need to take account of any religious and cultural beliefs that may have an impact on procedures. Such issues must be dealt with sensitively, whilst maintaining a consistent approach to the investigation.

- All professionals must record any history and background information given by parents or carers in detail. Initial accounts about circumstances, including timings, must be recorded verbatim.

- It is normal and appropriate for a parent or carer to want physical contact with their deceased child. In all but very exceptional circumstances this should be allowed with discreet observation by an appropriate professional.

- Parents/carers should always be allowed time to ask questions and be provided with information about where their child will be taken and when they are likely to be able to see them again.

- Parents should be informed that His Majesty’s Coroner will be involved and that a post-mortem may be necessary.

Appendix 3: Factors which may Arouse Suspicion

Some factors in the history or examination of the child may give rise to concern about the circumstances surrounding the death. If any of these are identified it is important that the information is documented and shared with senior colleagues and relevant professionals in other key agencies involved in the investigation. The following list is not exhaustive and is intended only as a guide.

Previous child deaths in the family

Two or more unexplained child deaths occurring within the same family is unusual and should raise questions both about an underlying medical or genetic condition as well as possible unnatural events.

Unexplained injury

Unexplained bruising, burns, bite marks on the dead child or a previous history of these injuries should cause serious concern. A child may have no external evidence of trauma but have serious internal injuries.

Neglect

Observations about the condition of the accommodation, cleanliness, adequacy of clothing, bedding and the temperature of the environment in which the child is found are important. A history of previous concerns about neglect may be relevant.

Previous child protection concerns within the family

Inconsistent information

The account given by the parents or carers of the circumstances of the child’s death should be documented verbatim. Inconsistencies in the story given on different occasions or to different professionals should raise suspicion, although it is important to be aware that inconsistencies may occur as a result of the shock and trauma of the death.

Also consider if any of the following are present:

- inappropriate delay in seeking help;

- evidence of drug, alcohol or substance misuse particularly if the parents are intoxicated or sedated at the time if the death;

- evidence of parental mental health problems or learning disabilities;

- domestic abuse;

- history or evidence of domestic abuse;

- presence of blood.